“Reading is the creative center of a writer’s life” – Stephen King

Hitting the Road:

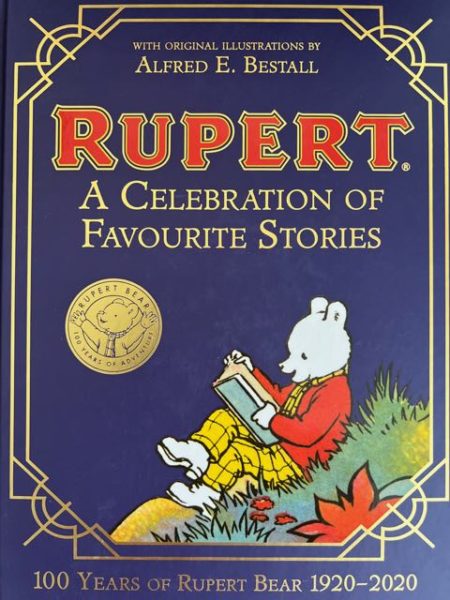

My journey to writing fantasy began at a young age when a relative of mine gifted me a Rupert Bear annual for Christmas. Rupert is an anthropomorphized—or humanlike—young bear who lives with his parents in a house in a fictional rural English village called Nutwood. Each annual is a collection of short children’s stories based off the same template: Rupert leaves home and has a fantastical adventure in an outlandish place such as King Frost’s Castle, the Kingdom of the Birds, the subterranean realm of mischievous elves, or at the bottom of the sea. Rupert and his pals have all kinds of escapades, but at the end of the story, they always return home safely.

What captivated me about Rupert’s world was the way otherworldly elements coexist side by side with the everyday. They include enchanted castles, wizards, sorcerers, magicians, imps, goblins, fairies, elves, dragons, medieval warriors, and the bird king, along with a band of anthropomorphic animal friends (animals with human behaviours, personalities, and traits) like Bill Badger, Edward Trunk, Podgy Pig, and Algy Pug. There are human characters, too, who live alongside the animal characters and treat them as peers: the old Professor (an inventor with a dwarf servant); the Chinese Conjuror and his daughter, Tiger Lily; Sailor Sam; The Sage of Um; and Rollo, the gypsy boy.

I loved these stories as a boy, which share a common format: comic strip illustrations of selected scenes, and below, two lines of rhyming verse that explain them. Underneath this, normal prose narrates the story in greater detail. Now and then there is a hand-painted picture depicting a scene of idyllic English countryside with hills, woods, and fields. These pictures have a “lost time and place” feel about them, a kind of nostalgia for a more innocent age in the 1920s and 30s, when the Rupert stories began as a newspaper comic strip.

Rupert’s escapades invariably involve the intrusion of the extraordinary into the everyday world, and the tension between them hooked me. They vary from the European fairy tales I’d been raised on: Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, and the like. Fairy tales are set in an ambiguous once-upon-a-time place and revolve around princes, princesses, nefarious queens, and forbidding forests—all of which were unknown in the part of West Yorkshire where I grew up. Don’t get me wrong—I loved these stories about fairies, ogres, witches, and enchantments. They have a clear-cut morality any child can understand. But those Rupert books are set in my world, not in some unreachable enchanted realm, and whilst not all characters in the stories are human, they are humanlike and felt real. I could identify with their motivations and emotions. And as many of Rupert’s adventures seemed threatening—getting lost, being held captive by criminals, being menaced by witches or other unnatural beings—they played on familiar childhood anxieties like separation, panic, and fear of the supernatural. In short, the plots, the characters, and the settings were relatable, and I read them over and over. Rupert books are a wonderful introduction to storytelling for young children.

Broadening the Mind:

As I grew older, my hunger for fantasy led me to a procession of books that included Gulliver’s Travels, Peter Pan, The Wind in the Willows, and The Chronicles of Narnia. In my early years, the fantasy books on shelves in bookstores and libraries were few and confined to the juvenile section. I wasn’t what you would call a bookworm, anyway. I spent most of my free time outside with my friends, playing sports or exploring the fields and woods that bordered our neighbourhood. But since children’s TV was modest back then and PC games hadn’t been invented, reading a book became my favourite indoor hobby. It was a gateway to worlds beyond my front door.

Adventure stories without paranormal elements, like Swallows and Amazons, appealed little, but it wasn’t until my teens that I stumbled across The Once and Future King by T. H. White, Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea series, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast series, Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising Sequence and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy. Others may have fallen under my radar, and so in search of more speculative fiction, I delved into a few horror books, like Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, plus the odd science fiction book by authors such as H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Isaac Asimov or the occasional dystopian novel by the likes of George Orwell or Aldous Huxley. However, with no internet to aid discovery, Tolkien remained unknown to me until I went to university, despite having studied English literature at grammar school. My teachers there never recommended fantasy novels, and the approved syllabus fed us a diet of “serious literature,” classics such as Chaucer, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Jane Austen, the Bronte Sisters, Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, George Elliot, Mark Twain, and Thomas Hardy, plus a handful of contemporary authors such as Harper Lee, J. D. Salinger, John Steinbeck, and D. H. Lawrence. All these authors wrote compelling stories about the human condition with characters that felt real, and I will always have huge respect for them, but they didn’t leave my imagination running wild. Only classes in Latin and Ancient Greek (compulsory grammar school subjects back then) filled that hole by introducing me to Homer’s Odyssey—an epic poem about a hero’s journey, mystical creatures, and gods.

Journey’s End:

By the mid-1980s, the fantasy genre had gone from being niche to mainstream, and its growing divergence of subgenres left me spoiled for choice. But I never lost my preference for stories where the natural and paranormal exist side-by-side—particularly those grounded in the mundane world, a throwback to those old Rupert annuals I’d read when I was young.

They say the road to writing is paved with a lot of reading. I think that is true of all genres, but especially when it comes to fantasy, because reading teaches the mind to imagine. That’s what made my first novel, Graëlfire fantastic fun to write. Of course, it’s about otherworldly characters that intrude into our world. There may be paranormal powers and forces at work, but this is a Grail quest at its heart with its setting grounded on Earth. The sequel, Graëlstorm is a leap into another world, a different universe. The heroine is transported from the human world to a supernatural realm, where she becomes embroiled in a clash between immortals that threatens her survival. Writing this book presented another set of challenges, because the story reaches beyond the natural, across the cosmos, to somewhere else, where the paranormal and supernatural are part of reality. Though this was a place I created out of my imagination, there had to be a reason and purpose for the paranormal and a credible logic that would explain my otherworldly characters’ actions, thoughts, and motivations.

The paranormal remained my key inspiration as I journeyed from reader to storyteller. In my fantasy worldbuilding, paranormal superpowers take the place of magic. I use the term “paranormal” rather than “supernatural” deliberately. I know to some people these words are interchangeable, since both are concerned with unexplained phenomena foreign to the natural world. But I make a distinction: to my mind, the paranormal has a secular quality, while the supernatural has more to do with spiritual beliefs. Superpowers, magic, wizards, and mythical creatures belong to the paranormal, while gods, angels, demons, souls, and the afterlife fall into the supernatural camp.

In that sense, my worldbuilding is paranormal with supernatural elements. It may be loosely based on Holy Grail and Judeo-Christian Gnostic myths, but its key elements are immortals, long-lived superbeings, and primal, otherworldly forces. There is a creative agency responsible for the Cosmos, but it is an impersonal force that is not worshipped as a god, and there is no institutionalized religion in my fictional reality. However, there are supernatural aspects, since my stories deal with the question of souls and the afterlife. That’s why I love writing speculative fiction. There are no limitations to what you can weave into a novel, be it wizards, ghosts, vampires, zombies, or any other form of mythical being or creature. As long as you tell a good story, the only limit is your imagination.

Since the beginning of time, the paranormal and supernatural have fascinated us, and storytelling has been a universal tool to explore that which we cannot see or explain. Whether through books, graphic novels, movies or games, interest in speculative fiction has soared. But for me, no form of storytelling is more enjoyable than those narrated through the medium of a novel. And to think, my journey began with the adventures of a little white bear!